[ad_1]

The scourge of wealth inequality is a global phenomenon. Perhaps the peculiarity of India is that the majority of the population, if only a few, are basically very poor. Few people become middle class in the world. Still, a minority of Indians rival the richest people on the planet.

Little is known about the changes in consumption and wealth distribution in India since 2012. The Indian government has binned the final round of consumer spending surveys (2017-18).

A recently released official sample survey of household assets and liabilities allows us to track changes in the distribution of household wealth. India’s National Statistics Office (NSO) produces a nationally representative and in-depth decennial survey of household wealth – the All India Debt Investment Survey (AIDIS). Surprisingly, the latest version of this data came sooner than expected and shows India’s wealth in 2018 (i.e. pre-pandemic).

A recently published working paper, The Sky and the Stratosphere: India’s Concentrated Wealth in the Lost Decade, examined changes in the distribution of household wealth from 2012 to 2018.

Our analytical results were surprising. We find that the inflation-adjusted loss of the 10% of the rich reduces wealth inequality. If this is true, much of the increase in inequality since the early 1990s (liberalization) will be reversed.

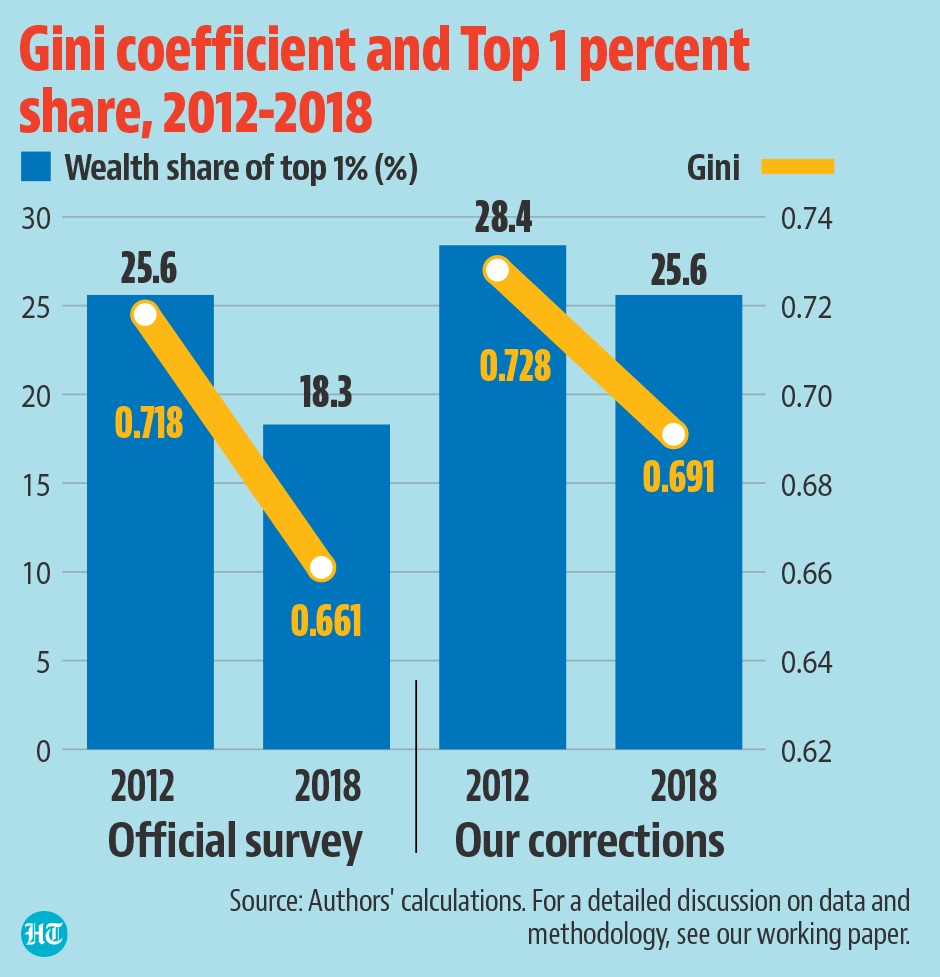

We show this using a common measure of inequality, the Gini coefficient. Gini coefficients range from 0 to 1. A value close to zero indicates a low level of inequality, and a value close to 1 indicates a high level of inequality.

According to official data, India’s Gini coefficient of household wealth per adult fell from 0.718 in 2012 to 0.661 in 2018. The wealth share of the top 1% (another measure of wealth concentration) also fell from 26% in 2012 to 18%. 2018.

In fact, wealth is so concentrated that a decline in the top affects average wealth. Survey data suggests that her per capita wealth in India declined during this period.

These results are surprising because no top-down redistribution policy was implemented between 2012 and 2018.

The biggest challenge is that the majority of Indians hold their assets in precious metals (gold, silver) and their prices have fallen substantially. The wealth of the richest families moved in tandem with the stock market, which performed moderately well from 2012 to 2018.

A closer look at the data suggests that official research overlooks the real rich.In our sample survey, the wealth of the wealthiest Indians in 2018 was ¥2.44 billion.But India’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani, was worth more than that, according to publicly available wealth rankings ¥250,000 rupees in 2018! The difference is orders of magnitude greater, and ignoring the actual wealth creates an illusion about the true distribution of wealth.

To account for rich, we recreated the distribution by adding rich using widely published wealth rankings. Our new dataset results moderate the extent of the decline, but most importantly, they also show a significant increase in the wealth of the ultra-high net worth.

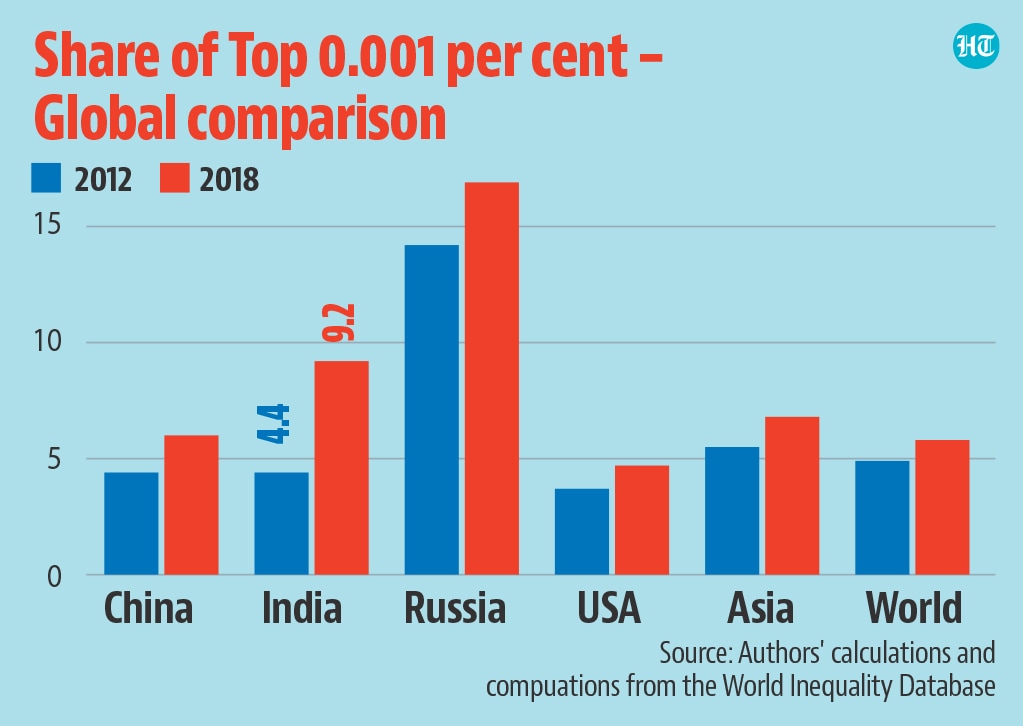

According to official survey data, the share of the wealthiest 0.001% of total wealth in 2018 was only about 0.34%. According to our results, the richest 0.001% of him own more than his 9% of his 2018 total wealth. It turns out that the wealth share of 0.001% doubled for him between 2012 and 2018. 350 million people.

How rich is India compared to other countries? We found that the top 0.001% of people in India have a higher wealth share than other major economies such as China and the US . In fact, India is second only to Russia in terms of the wealth share of the ultra-rich, an ominous development given the country’s notorious oligarchy.

Our findings have several implications. First, official surveys don’t seem to keep up with the actual wealth gains of the top tier. This is an important sign that the wealthy have been cut off from the skies (a limitation of research methods) and have ventured into the stratosphere. Accounting for elite wealth is essential to understanding wealth inequality. Elite wealth, that is, the wealth of the few who have astronomical wealth in a country where most people have little (if any) wealth.

Second, the time has come for inequality to become central to public policy discussions. For decades, policymakers in India have focused on the lower end of the income distribution, with poverty being the focus of discussion, while ignoring the concentration of wealth at the top.

It is abundantly clear that burgeoning inequality can no longer be ignored. It hampers efforts to reduce poverty, tackle climate change and preserve true representative democracy.

(Rishabh Kumar and Ishan Anand teach at the University of Massachusetts Boston and OP Jindal Global College, respectively.)

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now Read More

[ad_2]

Source link