[ad_1]

Due to the rapid growth of TPLFs and their increased involvement in litigation, cases often take a year longer to resolve than they would if a TPLF was not involved in the case.

This is the second part of a two-part feature on the commercial auto markets that was produced by actuaries with Milliman. Part one can be found here.

The TPLF Impact on the Bottom Line

According to Bloomberg, as of 2022, the TPLF industry is estimated to be worth approximately $39 billion worldwide. TPLFs such as Burford Capital are publicly traded, and college endowments have even taken shares in TPLFs.

Thus, TPLFs have “gone mainstream,” and there is no indication that the TPLF industry is slowing down.

While there are risks inherent in litigation funding, according to a report by Swiss Re, internal rates of return on litigation funds are up 25% in recent years. Further, despite the negative impacts of the pandemic, roughly $2.5 billion was invested into TPLFs in 2020, and investments grew by 16% in 2021.

TPLFs are so prevalent today that they often advocate in front of legislature and bar organizations and now have their own trade lobby, the American Legal Finance Association (ALFA).

Due to the rapid growth of TPLFs and their increased involvement in litigation, cases often take a year longer to resolve than they would if a TPLF was not involved in the case. But the additional time spent litigating the case is not necessarily producing a benefit to funded parties (i.e., higher recoveries for the plaintiffs).

One reason is that litigants who engage TPLFs usually see a return of less than half of the award or settlement amount.

Further, TPLFs appear to cause an increase in larger claims and thus are reducing insurability for companies. This has been observed in the commercial auto market where some insureds are choosing to obtain lower limits due to increased premium.

The simple addition of another party in litigation with decision-making power over a settlement increases the likelihood that a case will not settle, especially early in litigation.

For example, a plaintiff’s attorney on contingency might want to put minimal effort into a case in order to limit costs and maximize recovery, but if a TPLF is paying the bills, there is no such pressure for an early settlement.

As such, plaintiffs can now prolong litigation, which leads to additional costs and larger awards if the case gets past dispositive motions and close to a jury. Ultimately, the insurers may be forced to pay out higher claims or increased defense costs to defend a case longer.

The issues of increased claims and defense costs raise an interesting point of how policy limits may not cover these increased awards. While many large policyholders also obtain excess coverage, it remains to be seen whether even excess coverage will be sufficient.

And that lack of coverage can be exploited by TPLFs via the threat of post-judgment bad faith litigation to demand a full policy-limits settlement.

However, as the claims increase in cost, so do insurance premiums, and therefore policyholders are forced to bear the brunt of the cost. TPLFs therefore have a significant effect on how risks are underwritten in insurance policies. Insurers must now adjust to the presence of TPLFs, and this will require them to take into account the increased potential for large jury awards when assuming liability risks.

This also impacts reinsurance rates and the willingness of reinsurers to get involved in certain lines of business.

The commercial auto industry has noticed these premium increases. An ATRI study found that insurance premium costs per mile have increased by 47% over the last decade.

While not solely attributed to TPLFs, the premium increases continue to cut into transportation margins and impact the cost to move consumer goods, which ultimately creates an impact that extends beyond the courtroom and an insurer’s bottom line.

State of the Trucking Industry

American Trucking Associations (ATA) estimates that there is a growing shortage of truck drivers available in the market. They estimate that the shortage, as of 2021, was 80,000 drivers and that this number could climb to over 160,000 drivers by 2030 if the proper interventions are not taken.

There are numerous causes for this shortage, including such items as a high average age of current drivers, an inability of would-be drivers to pass drug tests (especially in states where marijuana is legal but still not allowed federally), and difficulty for drivers to spend extended lengths of time away from home.

Regardless of the cause for the shortage, it has created an environment of high driver turnover, given a multitude of alternate job options, and increased miles driven per driver.

It is also increasingly difficult for trucking companies to find and retain high-quality drivers, perhaps requiring fleets to settle for less experienced drivers.

The demand for trucking and the lack of drivers puts additional pressure on delivery timing, creating a thinner margin for error and requiring drivers to operate under tighter timelines.

Plaintiff attorneys are aware of the current environment and can build some of these points into their arguments to suggest that a trucking company should be held responsible.

For instance, it may be easier to say that the trucking company hired an underqualified driver or that the driver involved in the accident was overworked or undertrained. This paints the picture that trucking companies are irresponsible and not focused on safety, which in turn has the potential to lead to increased award sums.

Increasing Severity and Nuclear Verdicts

Figure 4 shows the average gross severity per reported claim within the first two years of the accident occurring for the 40 largest commercial auto writers as calculated from a composite of their Schedule P results.

Figure 4: Commercial Auto Reported Severity. Credit: Milliman

As can be seen in Figure 4, the severity of commercial auto reported claims has increased from around $5,250 in 2005 to nearly $9,900 in 2020.

Corresponding to the increase in severity since 2005, the commercial auto industry is seeing an increase in the number of exceptionally large claims.

For example, in Tomasa Cuevas, Alejandro Cuevas, and Maritza Cuevas v. Rai Transport, Inc., et al, a tractor-trailer ran a red light and caused an accident. In this instance, both the driver of the tractor-trailer as well as the owner of the truck were sued, and in 2019 the jury awarded over $70 million for both past and future pain and suffering.

In another 2019 case, Rebecca Lipton, Ivan Lipton, and Eva Lipton v. First Student, Inc., et al, which involved an accident between a school bus and a car. Both the school bus driver and the driver of the car were sued. They were both found to be negligent, and the jury awarded $36.5 million.

In another 2019 case, a jury awarded damages of $30 million when a driver making a U-turn onto a highway caused the operator of an oncoming vehicle to swerve off of the roadway into a parked tractor-trailer.

The parents of the deceased swerving driver sued the driver of the U-turning vehicle, the owner of the business from which the U-turning vehicle had just departed, the driver of the tractor-trailer, and the owner of the tractor-trailer.

These lawsuits are just a few examples of many recent nuclear verdict lawsuits. Nuclear verdicts are typically identified as cases that award $10 million dollars or more.

According to research done by the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI), in 2006 there were only four suits in the ATRI Litigation Database with awards exceeding $1 million. However, by 2013 over 70 suits had verdicts that exceeded $1 million.

The number of large cases subsequently decreased to a little over 30 suits by 2019. ATRI’s database shows a mean claim size of $3.2 million for cases settled between 2006 and 2019. The standard deviation of awards listed in the database is roughly $7.2 million, indicating that there is significant variability within the data.

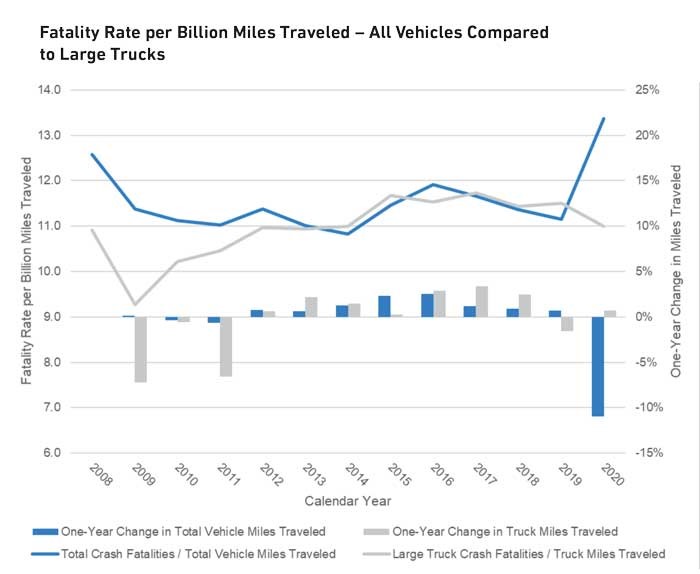

In many instances, nuclear verdicts are awarded in cases involving one or more fatalities. Figure 5 shows the fatality rate per miles traveled for large trucks compared to all vehicles.

It is worth noting that the rate of fatalities in truck crashes was lower than the total vehicle rate from 2008 to 2012. The fatality rates started to become similar around 2013, which is also when commercial auto loss ratios started to rise higher than the P&C industry.

Figure 5: Fatality Rate per Billion Miles Traveled. Credit: Milliman

Another interesting observation is that large truck fatality rates decreased in both periods of economic downturn (2009 and 2020); however, they represented different driving environments.

The global financial crisis resulted in significant decreases in truck miles traveled as the demand for goods slowed.

However, the pandemic saw a slight increase in truck miles traveled, though the decreased fatality rates in 2020 may have been due to fewer overall vehicles being on the road during the early months of the pandemic.

Thus, the large increase in the overall fatality rate in 2020 has been largely attributed to riskier driving behaviors and higher speeds that were more prevalent due to less road congestion. This phenomenon appears to have primarily impacted personal vehicles as the truck fatality rate moved in the opposite direction in 2020.

Worsening Reinsurance Results

Figure 6 shows the net and ceded ultimate loss and DCCE ratios (hereafter referred to as loss ratios) by accident year averaged across the 40 largest commercial auto writers as calculated from a composite of their Schedule P results.

The ceded loss ratios display the results of the reinsurers of commercial auto and capture the impact of an increase in the number of large claims.

As can be seen, both the net and ceded loss ratios have been on an upward trajectory since the global financial crisis with some improvements in recent years due in part to rate increases taking effect.

Figure 6: Commercial Auto Liability Ultimate Loss Ratios for Ceded and Net Business. Credit: Milliman

Perhaps the most interesting observation in Figure 6 is the transition from ceded ultimate loss ratios being historically smaller than net ultimate loss ratios to ceded ultimate loss ratios beginning to exceed net ultimate loss ratios in 2010, with over a 7% difference observed in every accident year after 2013.

Additionally, the reinsurers’ initial estimates of ultimate losses have generally been too low.

If these trends of high ceded loss ratios and consistent adverse development continue to persist, it is likely that commercial auto reinsurance rates will continue to rise.

The prevalence of higher ceded ultimate loss ratios is another indication that average loss amounts are increasing (assuming primary retention levels are remaining the same or increasing).

Solutions to Mitigate the Adverse Trends

1) TPLF proposed regulations

With nothing stopping the avalanche of litigation funding that is increasing congestion in the court system and driving inefficiencies, legislation may be necessary to limit attorney fees, prevent kickbacks and restrict TPLFs from involvement in certain underlying litigations.

Notably, New York state introduced a bill in 2021 that, if approved, would regulate TPLFs by placing a cap on the interest rate a TPLF can assess, preventing plaintiffs’ attorneys from collecting a referral fee, restricting TPLFs from having any control over the litigation, and protecting all communications under the attorney-client and work-product doctrines, among other proposed actions.

Additionally, the disclosure of the existence of litigation funders can be important to understand all the factors impacting a potential settlement. However, the large majority of U.S. jurisdictions do not require disclosure of TPLFs.

That may be changing as some courts such as the U.S. District Court of New Jersey have held that TPLF agreements must be disclosed during litigation. A federal court in California held similarly, while Wisconsin and West Virginia have also both passed legislation that requires disclosure.

Furthermore, requiring TPLFs to have more skin in the game (i.e., creating a potential downside) could also slow down the unfettered growth of TPLFs.

In any litigation, there is the possibility that a plaintiff is required to pay an award of attorneys’ fees and costs or potential damages for a counterclaim if a defendant is successful.

Thus far, TPLFs have mostly enjoyed only the upside after their initial investments and have not been responsible for paying these potential plaintiff fees. However, some defendants who seek recovery against a plaintiff who cannot pay may have an argument that the TPLF should be held responsible for any award.

2) Improved ratemaking/underwriting

Since long-haul trucking has been identified as one of the worst performing commercial auto segments, carriers have looked for ways to directly address these exposures.

Some carriers have looked to underwrite other vehicle types more aggressively or even move away from writing trucking business altogether. Other companies are looking for more innovative approaches to ratemaking to deviate from their competitors and better segment the risk.

Examples of this include building proprietary models that generate risk scores or underwriting tiers, developing enhanced zone rating or territory plans, and implementing usage-based insurance programs, typically utilizing mileage as an exposure base.

Telematics has also become more pervasive in the industry, which has allowed carriers to directly understand the behavior of individual drivers, as opposed to proxying it with fleet-level variables. Available telematics products range from more “traditional” telematics devices that collect driving maneuvers and location to camera systems that monitor a driver’s alertness or level of distraction.

The benefit of commercial telematics goes beyond insurance ratemaking applications. Many devices also come with fleet management tools that enable insureds to better train drivers and keep the safest drivers in their fleets.

Data and recorded video can also help reconstruct the conditions surrounding a crash, which could prove that a driver is not at fault or help insurers make better decisions about settlement strategies with the additional information.

While telematics programs have brought improvements to the commercial auto industry, there are still some hurdles to clear. High driver turnover can make it difficult to build and apply models at the individual driver level.

Also, some fleet managers are still hesitant to implement these systems, citing concerns over cost and increased turnover due to drivers not wanting to be monitored. Despite these hurdles it seems that telematics may be one of the clear solutions to better segment risk and improve commercial auto loss experience.

In Conclusion

In the absence of regulation of TPLFs, a reduction in inflation or an inflow of drivers to address the trucker shortage, we believe that the commercial auto market will continue to present challenges to insurance carriers.

To overcome these obstacles, insurance carriers will need to up their game with more sophisticated pricing models that better align rates with the corresponding risk, and with more enhanced risk management tools that help assess and train truck drivers. &

Brian is a Principal and Consulting Actuary for Milliman Inc., where his areas of expertise are property and casualty insurance. Christopher Fredericks is a partner at Mendes & Mount LLP. Drew is an Associate Actuary for Milliman Inc. with expertise in pricing, reserving and predictive analytics for various property and casualty exposures. Katie is a Consulting Actuary for Milliman Inc. with expertise in ratemaking, predictive analytics and loss reserve analysis.

[ad_2]

Source link